4. The Last Flight

The Vickers Viscount turboprop aircraft registered as N7405 began daily operations July 9, 1964 as United Airlines Flight 609. It departed from Raleigh, North Carolina that morning at 7:05 and, after stops in Washington D.C., Buffalo, New York, Elmira, New York, and Williamsport, Pennsylvania, was scheduled to land at 12:45 that afternoon in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

After landing on time in Philadelphia, the Viscount aircraft was no longer listed as Flight 609. Instead, the aircraft would be listed and resume operations as United Airlines Flight 823. Flight 823 was a regularly scheduled flight from Philadelphia to Huntsville, Alabama with stops in Washington, D.C. and Knoxville, Tennessee. A different crew would take over operation of the aircraft. Captain Samuel Huntington had been the pilot of the airplane earlier that day on the Washington to Philadelphia segment of the route. Huntington's First Officer was J.H. Thompson. One stewardess, Betty Jones, also served on Flight 609. She was to later testify in Knoxville, at the public hearing in January 1965. After landing in Philadelphia, Huntington would relinquish command of the aircraft to the airport's Line Maintenance Manager. Captain Oliver Sabatke and First Officer Charles Young would then take over command of the aircraft.

Flight 609 had operated normally on that day.

Huntington recalled, during testimony, that he had had a brief conversation with Captain Sabatke, whom he had known for several years while working for United Airlines. Huntington also testified that Flight 823's First Officer on that day was Charles Young. Huntington was Young's supervisor in Washington and he had spoken to Young about an upcoming evaluation and said that Young should stop by his office for a discussion. He mentioned that he and Charles Young had occasionally flown together. United Flight 823 departed Philadelphia at 3:13 that afternoon and reached Washington at 3:54. After normal servicing, the plane departed Washington at 4:36 with an expected 6:13 time of arrival that evening in Knoxville.

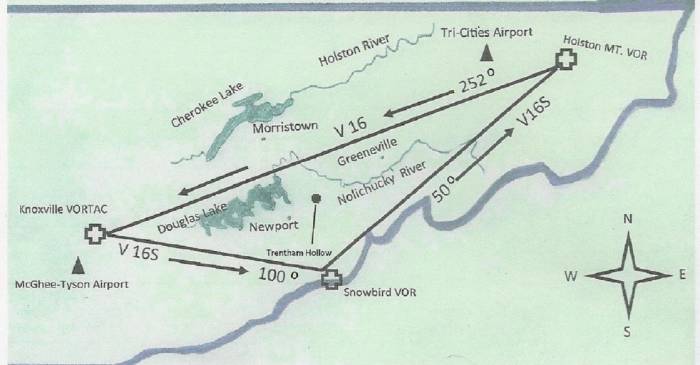

It had been a typical warm day in July. According to the CAB Accident Report the flight plan filed for Flight 823 showed it was to be routed along Victor Airway 143, Victor Airway 140 and Victor Airway 16 while under Instrument Flight Rules (IFR), at 14,000 feet mean sea level (MSL).

A Victor Airway is the designated Federal airspace that an aircraft flies between two points. Victor Airway 16 between the Holston Mountain navigational fix and Knoxville, Tennessee, was to be the last airway ever used by Flight 823. This section of airway is 92 nautical miles in distance. The final CAB accident report stated that air to ground communications that took place between Washington and Holston Mountain had been normal with “no discrepancies.” At 1758:35, which was a little past 5:58 in the afternoon, Flight 823 gave its position as passing Holston Mountain; with an expected time of arrival in Knoxville of 6:21. Atlanta Center responded by giving the flight an altimeter reading for Knoxville of 29:87 which was affirmed as being received by the flight crew. The crew of United 823 at 5:59:45 (fifteen seconds before 6 o'clock) then requested the “lowest altitude available.” The air traffic controller at the Atlanta Center then responded, ”…roger descend and maintain eight thousand now, over.”

United 823 responded, “leaving fourteen for eight”, meaning the aircraft had been maintaining fourteen thousand feet and would comply with the clearance to “descend and maintain eight thousand” given by Atlanta Center. Exactly three minutes later, at 6:02:45, Flight 823 called Atlanta Center and advised that they were cancelling their Instrument Flight Rules. This was acknowledged by Atlanta Center which suggested the flight stand by on that radio frequency until they were handed off to Knoxville Approach Control, once the flight was “a little closer in.” The aircraft's location was slightly past the Telford Intersection-about 20 miles southwest of Holston Mountain.

Ten seconds later, at 6:02:55, United Flight 823 responded “OK”. This is believed to have been the flight's last radio communication.

The unexplained last few minutes of the flight of United 823 was cause for those investigating the crash to spend a great deal of time going over the radio transmissions between the aircraft and air traffic control; while searching for possible indications of what went wrong. After a great deal of searching, I was able to locate transcriptions of communications and statements given by the principles tasked with air traffic control duties. These had become exhibits at the Knoxville public hearing which took place in January of 1965. There were no indications of anything being wrong with the aircraft during the time it was maintaining radio contact with Atlanta. Most notable, however, is the lack of two-way radio communication between Flight 823 and air traffic controllers during the ten and a half minutes after the last communication of “OK” and when the flight control official said he lost radar contact with Flight 823 “about eight to ten miles” southwest of the Ottway Intersection which was approximately 47 miles from Knoxville.

We have the tendency to look at the last known conversations, as transcribed, to find a possible indication of trouble. The request for the lowest available altitude, and the cancellation of Instrument Flight Rules to Visual Flight Rules that followed, were within regulations of the Federal Government and policies of United Airlines.

The weather in East Tennessee was good. The requests made by the crew of Flight 823 were not out of the ordinary. The aircraft would soon make its approach in to Knoxville. In the interest of safety, descent to eight thousand feet would allow Flight 823 to remain well above airspace “owned” by nearby Tri-Cities Airport and a continuing gradual descent, in the interest of passenger comfort, could be accomplished. We must first look at what we do know. The flight, since it was no longer flying IFR, was not required to navigate along the centerline of Victor 16 and could change its course as long as it stayed within the eight-mile width (four miles on either side of the centerline) of the Victor airway itself-which is known as “authorized airspace.”

It was suggested to the flight that it remain on “standby” on the Atlanta Center Frequency until the hand off to Knoxville Approach Control. My calculation is that when the aircraft responded to this communication from Atlanta Center with “OK”, it was approximately fifty-four miles from the position where the “closer in” handoff between Atlanta Center and Knoxville Approach would take place—at the Piedmont Intersection. The Piedmont Intersection is eighteen miles from the Knoxville VORTAC.

A map in the Flight Operations Manual gives the minimum altitudes for VFR flights along V16 as 6,000 feet for the nineteen miles between Holston Mountain and Telford, and 4,000 feet for the fifty-four miles between Telford and Piedmont intersections. It should be noted that these altitudes are “mean sea level” and within the confines of the minimum altitudes of the radar flight checks conducted for Atlanta Flight Center. Primary radar targets along the Victor 16 Airway, reflections off the surface of the aircraft, were good down to 6,000 feet, while secondary radar targets from the aircraft's transponder were good down to 4,000 feet. Once the aircraft reached the Piedmont Intersection, it would be below the radar minimums of 6,000 and 4,000 feet but would then be picked up by Knoxville Approach radar. As we know, the airplane did not reach Piedmont. The distance between Trentham Hollow and Piedmont Intersection, where it was customary for radar handoffs for flights approaching Knoxville using V16 to take place, was approximately thirty miles. The flight controller in Atlanta, in his narrative statement written the day after the crash, stated that he lost radar contact with Flight 823 at fourteen minutes after six o'clock. The controller stated that he attempted to contact the crew at that time; while advising them to change over to Knoxville Approach Control. Ten seconds later, after receiving no response from the crew, he attempted to contact them once more. There was no response.

Three possibilities for the lack of response occurred to the controller at that time. First, he thought the aircraft had descended too low for radar coverage—which at that point would have had to have been secondary radar targets from a transponder. Second, that the aircraft was too low to receive radio transmissions. Third, he thought of the possibility that Flight 823 had changed over to the Knoxville Approach Control Frequency. Stating that he was rather busy with other traffic departing the Knoxville facility, he did not give Flight 823 any further thought and was not notified that the airplane had not landed until about one half-hour later. There was no testimony I could locate that would help determine whether it was the primary or secondary radar target that disappeared first, but it must be assumed that the last contact that faded from the controller's radar scope had to have been from the transponder, as it had been flight checked to the lower altitude of 4,000 feet (msl).

The Civil Aeronautics Board Accident Report (Appendix pp. 136-151) became my constant source of information throughout the entire investigation—especially during the early days. It provided witness testimony that placed the position of the aircraft as flying at an extremely low altitude and approximately eight miles south of the Victor 16 Airway's center line—which the CAB, in its report, described as a “deviation”. The CAB was not able to come up with a reason for this deviation from Victor 16. In my estimation, Captain Sabatke had one or more reasons.

When I first began investigating United Flight 823, I discovered during a search of an aviation website that the pilot of Flight 823, Oliver E. Sabatke, was in the site's database.

I sent an inquiry to the aviation website with the basic information regarding United 823. I assumed I was going to receive additional information regarding the Parrottsville crash.

A few hours passed until I received an intriguing response that the website's data base only dealt with military accidents. This information came as a complete surprise. So, Sabatke, while serving as a U.S. Navy pilot, apparently had been involved in some type of different mishap many years prior to 1964. I mailed a check for $14 and waited for them to send a report.

Soon, something dawned on me. Captain Sabatke would have reached Douglas Lake, which is a man-made, forty-four square mile Tennessee Valley Authority lake, slightly north of Newport, Tennessee—if he had been able to continue to fly the aircraft westward another four or five miles beyond Parrottsville. Any passenger who has flown into Knoxville has looked out the window and viewed the large waterways that twist through the hills and valleys of Eastern Tennessee. Sabatke had flown in and out of Knoxville a number times, going back to his days with Capital Airlines. There was good visibility on July 9 and, at 500 feet above the ground, he would have seen Douglas Lake.

The requested report from the data base was slow in coming and, as I waited, I told myself that if it turned out that Captain Sabatke's 1944 military accident was one that involved him ditching a plane in water, in all likelihood, his final desperate minutes, twenty years later in East Tennessee, had been spent in an attempt to safely land the plane in or on Douglas Lake.

The official United States Navy report arrived, and I was not disappointed. The photocopy was in poor condition, but the clearest words stood out and said, “While in traffic over tower, engine conked three times. Emergency fuel pump was on. Engine went dead completely. Attempts to revive with primer were useless. Downwind water landing was safest compared with straight ahead open sea landing or lagoon because of boat pool small craft.”

The reason the photocopy was in such poor condition is because the original had been more than likely typed in poor conditions, as one would find in a war zone. Ensign Sabatke had been flying a training mission in a Grumman F6F-3 Hellcat (#42537) on the Eniwetok Atoll in the Marshall Islands on November 30, 1944. On another section of the report I read the words: “Plane sunk in ocean.” My position on how Captain Sabatke spent his final moments can be described as speculative. I would be the first to admit it. But, how far-fetched is it when one considers the keen survival instinct that is present in all humans, especially when one finds himself in such daunting circumstances? The general topography of the area did not favor a ground landing.

The CAB report mentions Flight 823 deviating from the Victor 16 Airway. It did not reach any conclusion as to why. I'm left to wonder how much of the Captain's background was investigated and discussed. I say this because, as I later found in my investigation, there were certain facets in Sabatke's aviation background that tend to favor the opinion that I have formulated. Most importantly, I was to later discover that Captain Sabatke had flown amphibious aircraft as a U.S. Navy pilot during World War II.

In the final analysis there is no other way of looking at it—especially in light of the fact that, as a young U.S. Navy Ensign, Sabatke had taken the only course that was available to him on Eniwetok Atoll: The water was the best place to land his airplane.

Since the beginning of the United 823 project, I was most concerned about how my work would be received by the surviving family members. I also reasoned that those whose loved ones perished on that day, would have the greatest amount of interest in what I was attempting to accomplish. At the same time, I thought one should not embark on such a project with assumptions.

My mind was occupied by a realization that any success that could be attained by me was contingent on being accurate. This also led me to understand the possibility that my work could be the topic of discussion, not only among family members interested in gaining information as to what happened, but by others who had actual backgrounds in aviation.

The more I have become familiar with the workings of aircraft and the general skills of those involved in the airline industry, I have come to realize that there is no room for airline crews, mechanics, air traffic controllers or any others involved in the airline industry to make mistakes. The same applies to the project I have undertaken.

Sensationalism has no place in the work I am doing. When I first began my research, some of what I found in various online places had to do with the paranormal. I'm reluctant to dwell on the topic, except to say that, in my opinion, capturing someone's imagination with claims of ghosts and haunts does not involve the skills and patience that are necessary in doing thorough research. I have taken this project seriously. The last thing I have intended is to be a person who second-guesses anyone. However, there may be times when certain questions raised by me may give that appearance. Always present in the back of my mind is the realization that some, with whom I may disagree, are no longer alive to defend themselves regarding their findings.

The opinion that Captain Sabatke intended to land the stricken aircraft in Douglas Lake may be viewed as a form of sensationalism. However, instead of grasping at thin air, I reasoned that Captain Sabatke's primary concern was finding the best place to land the aircraft. My personal knowledge of the local topography leads me to the conclusion that there were no other options available on that day. The low altitude of the aircraft leads me to believe that Sabatke, without benefit of ground personnel guiding the aircraft in for a landing, had to make sure that he had the proper distance to complete a safe landing.

The landing gear, as found in the wreckage, was in the retracted position, according to the CAB accident report. The landing gear in the “up” position would have been necessary for a water landing. Eventually I received additional information about Captain Sabatke's experience in the United States Navy as a pilot who not only had survived the crash landing of one aircraft; but he had also logged nearly 1,500 additional hours in amphibious Catalina PBY aircraft in the Pacific Theater during World War II. I became more convinced that he “deviated” from the Victor 16 Airway to make a water landing. {Captain Sabatke's experience with PBY amphibious aircraft is discussed in another chapter}

Again, had anyone considered the Captain's experience as a military pilot?

The Atlanta Center Air Traffic Controller, in his narrative statement of July 10, 1964, stated that he was occupied with other flights departing Knoxville. Two different flights were to depart from Knoxville at the same approximate time that United 823 was to make its approach. One flight departed Knoxville at 6:08 Eastern Standard Time; while the other departed at 6:09. The assigned route for takeoff for these two aircraft was Victor Airway 16 South-not to be confused with Victor 16 Airway from which Flight 823 had “deviated” to the south and closer to the flight paths of the two aircraft that were departing Knoxville.

Aircraft using Victor Airway South, out of the Knoxville Airport, would begin by heading in a general direction of southeast on a heading of 100 degrees, slightly south of Douglas Lake and Newport, Tennessee.

Just short of the Tennessee/North Carolina state line, aircraft leaving Knoxville on V16 South would bear to the left in order to re-establish themselves on V16 South, on a different heading of 50 degrees-which would have the aircraft traveling in a more northeasterly direction. The V16 South centerline is slightly south of Bird's Bridge on the Nolichucky River. Witnesses, Judge Wayland Harrison and Dan Burgner, have established the presence of United Flight 823 near Bird's Bridge. It can be presumed that both aircraft leaving Knoxville, without the knowledge of their respective flight crews, were headed in a direction that could have caused a mid-air collision with Flight 823.

Victor Airways were eight miles wide—four miles of width on either side of the centerline. Under normal flying conditions, there would have been ample distance between Victor 16 and Victor 16 South, but it has been established that Flight 823 had “deviated” about eight miles off the centerline of V16; which means that Flight 823 was in position four miles south of the outer reaches of its assigned airway. This position had the potential to place the aircraft four miles closer to the two aircraft that had departed Knoxville on Victor 16 South.

A question to ask is, once the United 823 crew decided that the situation on board the aircraft was becoming dangerous, was their concern to simply get out of the way of possible air traffic in its own designated air space along Victor 16 by deviating the four miles, while, at the same time, flying at a lower altitude in order to make sure it was avoiding any out-bound air traffic flying out of Knoxville along Victor 16 S Airway? In addition, if one drew a line on a map from Bird's Bridge to the Knoxville VORTAC it would indicate that there are no obstructions, such as mountains, that would interfere with the Flight 823’s navigational equipment that was dependent on line of sight to function properly.

It must be remembered that outbound traffic from Knoxville was also subject to observing air space, to the Northeast, belonging to Tri Cities Airport. By the time outbound flights had traveled the approximately forty or fifty miles along their assigned Victor Airway 16S, they were required to be above the same 7,000 feet that “belonged” to Tri-Cities airspace.

Sabatke had to have known that he had veered south from Victor 16 Airway. Besides giving him the chance of landing the aircraft in Douglas Lake, a loss of altitude, therefore, would also allow him to avoid out bound traffic from Knoxville. Likely, as a pilot who was accustomed to flying in and out of Knoxville, Sabatke had to have been aware of a possibility that traffic was leaving Knoxville and heading in his general direction.

Map is not to scale.